Program

Dieterich Buxtehude (1637-1707): Passacaglia in d minor, BuxWV 161

Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643): Toccata terza, per l’elevazione, from Il secondo libro di Toccate (1627)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791): Andante in F major for musical clock, K. 616

Johann Ludwig Krebs (1713-1780): Chorale prelude: “Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott”

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750): Pièce d’orgue, BWV 572

From the Performer

It is rare for me to stay in one place for long. I can’t remember another time in my life when, for weeks and months, I’ve not travelled to play a concert, do research, visit friends or family. And there’s a danger when staying in place, I’ve found, of coming unmoored in time. Much of the music I’ve gravitated towards these past months seems to reflect on a state of suspension, an interest in, indulgence in, even, the failure to move forward.

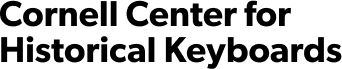

Playing the organ during this time, I’ve thought about 20th-century French composer Jehan Alain’s mesmerizing miniature Le Jardin suspendu (The Suspended Garden), at the top of which Alain writes “The suspended garden is the artist’s ideal, perpetually pursued and fleeting; it is the inaccessible and inviolable refuge.” Alain’s dreamy evocation of the tension between pursuit and stasis at the heart of the artist’s endeavor, which is worked out in the form of a baroque chaconne, is better suited to the Aeolian-Skinner organ in Sage Chapel, with its capacity for blurred and distant sonorities—and I’ll save it for a future performance there. But it lies at the heart of the program I’ve conceived here for the brilliantly distinct and vivid Cornell Baroque Organ in Anabel Taylor chapel.

Each of the pieces on this program reflects in some way on suspended states, yet each simultaneously thrums with energy. Likewise, the glorious organ in Anabel Taylor chapel, while the ultimate place of refuge from the outside world (for me, at any rate), is an instrument that bursts with musical potential and visceral sonic excitement. We hear that energy beating through the Buxtehude Passacaglia, belying the circularity of the piece’s constantly repeating bass line; and in the rhapsodic wanderings of the Frescobaldi Elevation Toccata ecstatic timelessness is punctuated by sharply symbolic Lombardic rhythms and pointed fragments of forward-moving counterpoint. In a rather different mode, Mozart’s Andante, K. 616, a musical creation for a small mechanical organ in a clock, is all about time and time-pieces—for all its elegance and grace, its repetitions, reiterations, trills and frills suggest the automatic and continuous functioning of the machine that will keep on running until the mechanism winds down. In the beautiful chorale prelude, Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott (We all believe in one God) by J. L. Krebs (a piece previously ascribed to J. S. Bach) the timeless certainty of the Lutheran creed emerges from the elaborated chorale melody in the right hand (here played on the 8’, 4’, and 3’ flutes on the Hauptwerk), as it unfurls over two voices in the left hand (here played on the Hautbois on the Rückpositiv in a duet between two oboes d’amore) and two independent voices in the feet—a double pedal part that demands that the organist be literally suspended in space at the organ console. Finally, J. S. Bach’s Pièce d’orgue, with its opening burst of brilliant energy, its momentous central exploration of harmonic suspensions at almost unbearable length, and then its virtuosic welling-up of wave after wave of sound in rushing passagework to the final cadence, plays out an inevitable confrontation between inexorable suspension and the greatest musical vitality.

When you have music like this, and an instrument like the Cornell Baroque Organ at your fingertips, there’s really no need to go anywhere else.