Program: All music by J. S. Bach

Chorale Prelude: “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme,” BWV 645

Chorale Prelude: “Nun komm’, der Heiden Heiland,” BWV 659

Canonic Variations on the Christmas Hymn “Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her,” BWV 769a

Toccata and Fugue in F major, BWV 540

From the Performer

Bach’s oeuvre for the organ is rich with music for Advent and Christmas, diverse in style, genre, complexity, and color. The chorale prelude on “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme” comes from the late collection of Sechs Choräle von verschiedener Art (Six Chorales of Various Kinds) published in 1747-48, a popular set known by the name of their publisher, Johann Georg Schübler. Like most—or perhaps all—the pieces in this volume, the setting of “Wachet auf” is a transcription of a cantata movement. In the well-known organ version, the lively ritornello originally given to the unison violins and violas is taken in the right hand, accompanied by the pedal’s continuo line, while the tenor solo, sounding out the chorale melody in plain long notes, is played by the left hand (here on a solo trumpet stop). From the eager anticipation of “Wachet auf” we move to “Nun komm, der heiden Heiland,” the hymn that marked the start of the Church Year in Bach’s 18th-century Leipzig on the first Sunday of Advent. In a somber G minor, the slow-moving accompaniment undergirds the chorale melody, ornamented nearly beyond recognition from its austere Gregorian origin: the bass moves inexorably towards Christmas, the light of the Gentiles flickering and feinting above.

Bach’s five Canonic Variations on the Christmas Hymn “Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her” (“From Heaven Above, I Come to Earth”) appeared in 1747 at about the time of the Schübler chorales. In the Canonic Variations, Bach pursues intricate contrapuntal combination to unsurpassed levels of complexity, while clothing these investigations in a style as engaging as that of the galant Schüblers. This scholarly, yet stylistically fashionable, display remained largely hidden to casual listeners, but was dauntingly impressive to those with the score, which survives both in autograph and the original print. The research in Bach’s contrapuntal variations marked his admittance as the 14th member (14 being the sum of B, A, C, H in the number alphabet he made abundant use of) of the Corresponding Society of the Musical Sciences founded by his student Lorenz Mizler. Handel had been admitted to the group two years earlier. The first two variations are relatively straightforward, at least by Bachian standards, with clever and elegant two-voice canons played by the hands at the interval of an octave and then a fifth, above the hymn tune heard in long notes in the pedal. The exuberant third variation (as found in the order of the autograph version heard here) treats the hymn tune itself in various canonic formations above a rollicking pedal bass, then adds a florid line that sweeps through the manuals, with the free fingers combining with the feet in treating the hymn in still more canonic schemes. A dense stretto layering the individual phrases of the hymn on top of one another commences when the pedal arrives at its last, lowest note; in the final measures Bach stages a crescendo of added voices, and signs his name B-A-C-H in a proud flourish. The fourth variation is a suave Cantabile with the pedal and left hand weaving a canon at the unlikely interval of a seventh, below a flickering, fashionable obbligato in the right hand charged also with managing the periodic entries of the chorale melody. The last variation presents an augmentation canon in which the florid soprano line bolts ahead at twice the pace of one of the left-hand accompanimental parts, the distance between the canonic lines quickly and relentlessly expanding beyond the limits of aural perception. It all sounds more like an unbounded fantasia, not a terrific feat of asynchronic exactitude. In the culminating bars the newly-minted Musical Scientist signs his name again, first in the proper order (B-A-C-H) then in retrograde (H-C-A-B) as the ecstatic soprano line rises towards heaven.

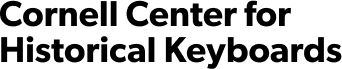

Our organ in Anabel Taylor has been sounding now for a decade; it was in the spring of 2011 that we dedicated the instrument, but in November 2010, after months of voicing each of the nearly two thousand pipes by Munetaka Yokota, our adviser Jacques van Oortmerssen played, with us, the first public concert. Much Bach has been played on this nonpareil Bach organ since. But not all of his massive catalog: this Advent Midday Music presents the F-major Toccata and Fugue for the first time. That it has not yet been attempted on this instrument till now has to do with the compass of keyboards, both for the hands and the feet. Bach wrote the Toccata for a celebrated organ in the ducal town of Weissenfels (where he met his second wife Anna Magdalena Wilcke), a singular instrument because it boasted a compass that added several notes to the upper end of the pedal and manuals—a setup criticized as wasteful excess by some contemporary commentators. Bach exploits these added keys in several raucous manual chords, but especially at the literal highpoint of the second of two aerobic pedal solos that burst forth from epic drones above which ecstatic canons swirl.

Bach’s favorite student, Johann Ludwig Krebs, adapted these and other passages to the usual, more modest compass, and since our organ (unlike almost all neo-baroque organs in north America, which mimic Weissenfels on account, no doubt, of the F-Major Toccata alone) sticks to the 18th-century norm, the version heard here takes some of Krebs’s tricks for adaptation and adds others.

The drones are drawn from the genre of the pastorale, a favorite of German organists at Christmastime evoking the shepherds with their shawms, but in this hair-raising Toccata we hear them elevated and expanded to sublime proportion and energy. Right from the start the piece can barely be contained by its bucolic setting: Bach busts loose from the harmonic and contrapuntal framework he sets up and launches into a runaway concerto that charges past cadences and plays dangerous high-speed games with the sequences and drones heard at the outset, before slamming past—or perhaps into—the finish line.

The Fugue (which is not transmitted with the Toccata in many manuscript sources) begins as a stately oration of antique cast, then lets the pedal have a lengthy rest while working out a more spirited second subject in the manuals. The feet at last return for the authoritative, dramatic combination of the two themes, a thrilling summation of Bach’s only fully-developed double fugue for organ—and a learned, enthralling sermon in sound for Christmas.